originally published in The Cincinnati Review, 11.1 (2014), winner of the Schiff Award for Prose (2013)

I thought I would move this essay to Substack given the horrendous air quality from the fires in Canada. When I wrote this piece, I wanted to explore apocalyptic religion and climate change — and it still holds true a decade later.

My first summer in Zion, the Mormons deliver a latter-day miracle.

A grasshopper plague is encroaching on a town somewhere out there in the vast Utah emptiness, on the other side of the Great Salt Lake: two thousand grasshopper eggs to the square foot, little exoskeletons bursting into being from thin air, like popcorn kernels on a hot burner.

Local news Channel 4 bears witness: Every ten years, the grasshoppers come. Like clock work.

As an outsider, a Gentile, I have made this reporter my hierophant. The Mormons have their Prophet, Seer, and Revelator, and I have a newsman. I never watched local news before moving here.

The plague is supposed to happen.

Backyards are popcorn machines, pop, pop, pop.

Insecticide has failed us.

The seagulls — the same birds that saved Mormon pioneers from the grasshopper plague of 1848 — have forsaken us. But not all of us. One lone believer prayed for a miracle, and seagulls swooped in to devour the pestilence. “It was my faith,” she says. “The seagulls came because of my LDS faith.”

LIVE FROM GRANTSVILLE, UTAH: God has not forsaken us in these latter days. We are still his people, the peculiar people.

But what if the miracle is the other way around? What if the miracle is the grasshoppers?

“I want hard times,” Brigham Young proclaimed, “so that every person that does not wish to stay, for the sake of his religion, will leave.”

The plague is supposed to happen.

Zion is not a city. It is a terrestrial docking station for the heavenly Zion when it descends at End of Times. I used to imagine it hovering like the mother ship in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a glittering, saucer-shaped metropolis in the clouds, skyscrapers sprouting out the top, twinkling lights arranged around a center iris. When Zion appeared, the golden Angel Moroni statue atop the Salt Lake Temple would come to life, blow his trumpet, and herald the apocalypse. The temple spires would light like a runway control tower, signaling to God: This is the place.

I committed the classic Gentile mistake: ascribing too much power to God and not enough to humanity. Zion does not wait passively like a lightning rod. It is not a candle in the window for Heavenly Father. It is a writ of extraordinary relief, a direct appeal to the highest authority: Appear in our jurisdiction. Heavenly Zion “can come only to a place that is completely ready for it,” Mormon scholar Hugh Nibley writes in Approaching Zion. “When Zion descends to earth, it must be met by a Zion that is already here.” The world does not end because we are bad; it ends because we are good.

Latter-day in the Church of Jesus-Christ of Latter-day Saints means last days. Mormons must concentrate at all times on the end, as Zion does. It is why they stockpile macaroni and cheese, Cheerios, powdered butter and milk, soup, water, toothpaste, candy, shampoo, deodorant, gasoline, generators, flashlights, batteries, and bullets. Their minds and hearts must be microcosms of the City of God.

Like attracts like.

One Mormon becomes an object of fascination on CNN when he shows off his underground bunker blasted into a mountain slope, stocked with canned food, firearms, and gold for the apocalypse — not because he fears it, but because he wants it. He does not pray, “Spare us.” He prays, “Give me advance notice.” He is leaning air stairs against the stars.

Since moving to Salt Lake City, my husband and I have started our own stockpile in a spare room: twenty-five pound buckets of oats, butane canisters, a portable stove, gallons of water, batteries, flashlights. We started it because the city is overdue for a catastrophic quake along the Wasatch Fault, and when the fault ruptures, the east benches will drop off the mountains, tilting the valley floor like a pitcher, pouring out the Great Salt Lake.

“Americans hate the Mormons,” I say to my husband after a news segment about the fault. When we first arrived here, Facebook friends regularly posted polygamy jokes on my wall. One called the Angel Moroni the Angel MORON-i. “Nobody will save us.”

Not long after that, my husband purchases an AR-15 and locks it in a gun safe. In a backroom closet, he stacks ammo boxes like bricks.

Can a city, by design, make you long for the apocalypse?

The Mormons have a saying: As long as you can see the temple, you are never lost. They mean this literally. On Salt Lake Temple, the Big Dipper carved into the west tower is in perfect alignment under Polaris, the North Star. As Polaris sits at the center of the clock dial of the stars, the temple sits at the center of Zion. The temple is meridian zero: the point from which all streets radiate, a spiritual and navigational compass. Almost every downtown address expresses latitude and longitude in relation to it: 200 S 500 E translates to two blocks south and five blocks east of the temple.

As long as you live in Zion, you know how far you have strayed from Heavenly Father — and how to get back to him. In this sense, as Nibley describes in the Meaning of the Temple, the temple is the “knot that ties heaven to earth, the knot that ties all horizontal distance together, and all up and down, the meeting point of the heavens and the earth.”

In the temple, man climbs back to the presence of God through the endowment: washing and anointing; a ritual drama of the creation and the garden of Eden; learning the signs, keys, and tokens to reach Heavenly Father in the afterlife, and finally, passing through a veil into the Celestial Room, symbolizing the presence of God. It is the fall of Adam in reverse. It is atonement.

“Notice what atonement means,” writes Nibley: “reversal of the degradative process, a returning to its former state, being integrated or united again — ‘at one.’ What results when particles break down? They separate. Decay is always from heavier to lighter particles. But ‘atonement’ brings particles back together again. Bringing anything back to its original state is at-one-ment.”

Atonement is the opposite of entropy, the opposite of the natural order of things, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which dictates that things fall apart.

The temple, then, is an anti-entropy machine.

This is also why Joseph Smith — he would say God — designed Zion to be so compact and dense: one square mile, a maximum of twenty thousand residents; ten-acre blocks with twenty half-acre lots each; eight people per lot. “When the square is thus laid off and supplied,” he declared, “lay off another in the same way, and so fill up the world in the last days” — a divine urban-growth boundary. He knew if Mormons strayed off the plat, they would wander off God’s map and onto man’s. Zion would dissolve. The center could not hold.

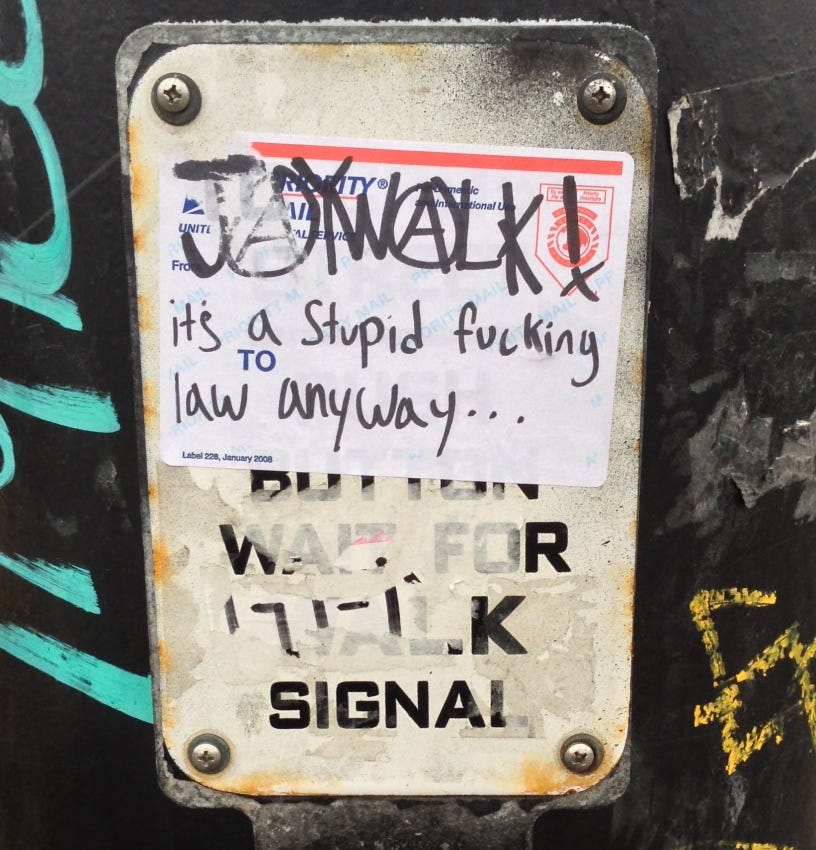

In Salt Lake City, vandals mount insurrections on the crosswalk poles:

Crosswalks are Zion’s Achilles’ heel, the intersection of what was and what is. When Brigham Young designed the streets 132 feet wide so oxen team drivers could turn around “without resorting to profanity,” he did not know he had exposed Zion to a fatal flaw: “wide, wide forever wide streets,” as Norman Mailer described them, ready-made for cars. The automobile was the anti-temple, a force of entropy destabilizing Zion’s crystalline structure. Zion dissolved, sprawling across the valley. The center could not hold. The population of Salt Lake City today: 189,314. Population of the metro area: 1,126,982. How many of those people can see the temple — actually see it?

“Even the smallest impurity or flaw in anything designed to continue forever would, in the course of an infinite stretching of time, become a thing of infinite mischief,” warns Nibley in What is Zion? And yet, Joseph Smith received the designed of the Zion Plat by divine revelation, and Brigham young was his spiritual heir — a Prophet, Seer, and Revelator, too. How could God telegraph to his chosen people a blueprint tainted with a fatal flaw?

I am, of course, committing my classic Gentile mistake once again: ascribing too much power to God and not enough to humanity. Zion can only come to a place completely ready for it. The streets had free will paved right into them from the start: You can U-turn. You can turn away. People chose cars, not God’s blueprint. Today, Salt Lake City is so car-obsessed that pedestrians risk life and limb to cross downtown streets. The city resorted to installing cups containing hazard flags on the crosswalk poles. Signs implore, “Take one for added visibility.” I refuse to submit to that lie.

At first, when JⒶWⒶLK appears on poles in my neighborhood, the graffiti seems like a force of entropy, too. If God were real, the vandal writes, tipping his hand: He is a nonbeliever, inciting pedestrians to revolt. And yet even he longs for the original Zion, the one designed for God’s people — emphasis on people — not cars.

Maybe, just maybe, the blueprint contains no flaw at all. Maybe this was supposed to happen. “One does not weep for paradise, a place of consummate joy,” writes Nibley, “but only for our memory of paradise.”

How can you atone without falling apart?

We are not canaries in the coalmine. Stop driving for the fucking air! — gas station graffiti

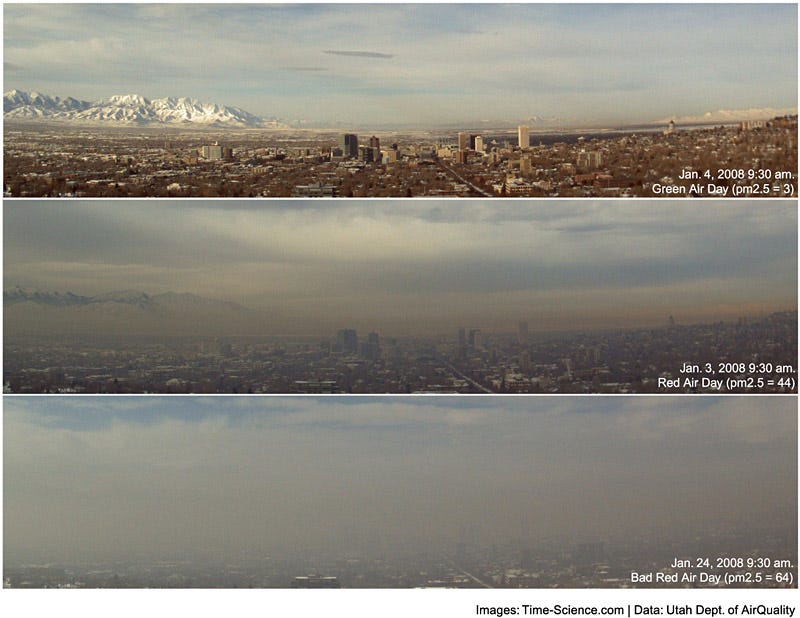

In winter, Zion becomes the bottle city of Kandor: entombed inside a fortress of solitude, breathing its own private atmosphere. The same mountains that insulated pioneer Mormons from persecution in 1847 turn traitor, trapping cold, stagnant air in the valley. Warmer air floats over their peaks, sealing the city inside an invisible bell jar. Meteorologists call the phenomenon an inversion because it flips the natural order: cold air near the ground and warm air high above. Heaven and earth trade places.

Here in the Bottle City, soot and particulates from power plants, automobiles, oil refineries, incinerators, and wood-burning stoves build up like exhaust in a locked garage, thickening into smog so dense it leaves a film on my teeth and hair, so caustic it sears my tonsils and throat. It tastes like a dirty penny. It gloms on to my vocal cords, corroding them until I sound like an old menthol smoker. Sometimes I cannot speak at all. My nostrils burn. My snot thickens into acidic goo.

Under the bell jar, the city is airless, windless, a kind of vacuum. Sound ceases. Winter birds hop along tree branches, beaks opening and closing, but I hear no song. Children scream and giggle, but the sound reaches me as though I am underwater. Barking dogs sometimes break through, but as in a dubbed film, their muzzle movements do not synch with the sounds. You would think smog could carry sound, that all those heavy metals would transmit it as clear as a telephone wire, but it does not.

The Utah Division of Air Quality calls the particulates PM2.5, meaning 2.5 micrometers in width, roughly 1/30th the width of a human hair, tiny enough to penetrate into the deepest lung tissue. Most of them are secondary aerosols: NOx from automobile combustion reacting with ammonia and other volatile organic compounds. NOx stands for nitrogen oxides: x as in algebra. Add to these molecules the intense UV radiation at Zion’s elevation of 4,300 feet, and a photochemical process gets sparked that cannot be stopped. The process is mathematical, predictable, exquisitely ordered: intelligent design. Even air-quality scientists call the chemicals species, as though they are living things, with volition and will and minds. When I walk through the smog, I am not just walking through toxic air; I am walking into a cloud computer, a sentient force.

NOx is unstable, as are all volatile organic compounds. Unstable atoms seek stability, order, an end to entropy: this is why they pair up, marry, give birth to new particulates. A microcosmic Bing Bang is happening right before our eyes. The smog is primordial soup, the stuff of new life: an inversion of the normal order of things, an insurrection against the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Meteorologists blame the earth for the air: the strange topography of Zion, the mountains in all cardinal directions. Locals blame the air for the air. They call it bad air, as though it perpetrates evil. Never pollution, only bad air. “If it was the cars,” they say, “the air would be like this all the time, but it only happens in winter.”

They are wrong. In summer, we are a bottle city, too. Air stagnates then as it does in winter, except somehow Zion stays sealed inside with no lid to hold it. The sun beams down as omnipotent as a nuke, breaking apart molecules, accelerating reactions between NOx and volatile organic compounds to generate ozone.

Even with no temperature inversion, we are still breathing inverted air: stratosphere becomes troposphere. The same ozone that saves us from radiation high above kills us down below, rapid-aging our lungs. We cannot breathe the same air as God. And once the cycle begins, it perpetuates until molecules have no more atoms to give, ticking down like a doomsday clock.

They can blame the mountains and the air. I blame the temple.

The temple is yanking heaven down to earth by its knot, pulling it into the bottle like a model ship. The anti-entropy factory is working. It is holding air together on earth as it is in heaven. Unstable atoms fall apart; atonement brings them back together again.

I breathe the inversion in; I breathe it out — and just by entering my lungs, the air has changed composition once again. Simply by breathing, I am complicit in the cloud computer. I am co-creator of the intelligent design. I am quickening the apocalypse.

I am atoning.

January 2013: The Mother of All Inversions descends, choking off the Bottle City from fresh air for weeks. NBC News with Brian Williams finally picks up the story — the first national outlet to cover it.

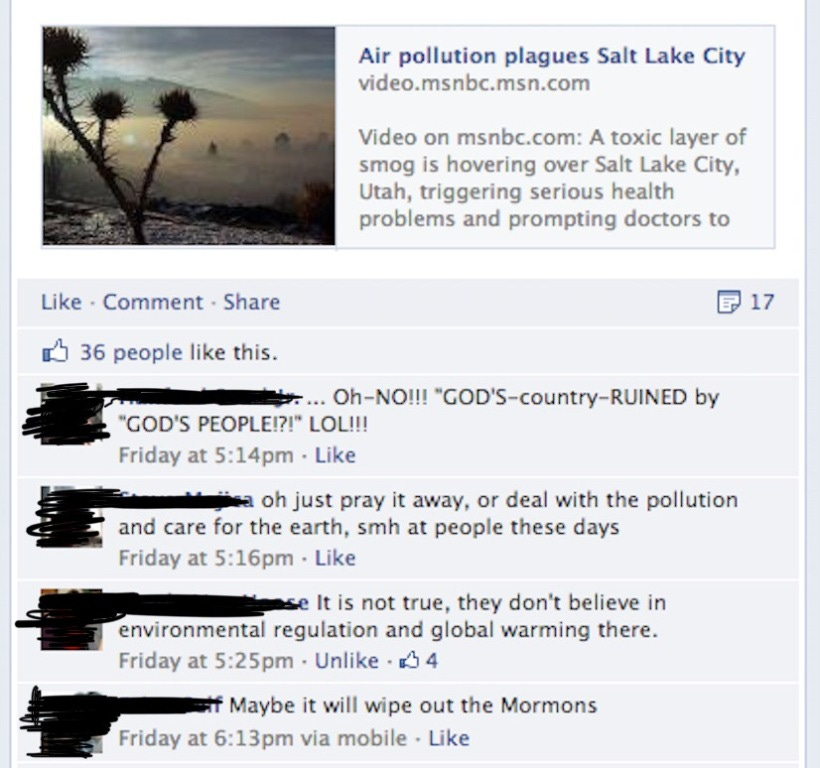

On Facebook, my fears come true:

We will die here, I think. Superman is not coming. Americans hate the Mormons.

Then I catch myself thinking, Good. We are still the peculiar people. The chosen people.

We.

When I first moved to Utah, I mistook the Bingham Canyon Mine for a volcanic crater. Later, I thought it might be a desert plateau because the rust-colored marbling around the crater walls reminded me of the painted hills in the eastern Oregon desert. Then I thought it was a rock quarry. Then a meteor impact site. Then a nuclear crater from the days of atomic blasts in the American West, even though I know the mushroom clouds bloomed over Nevada, not Utah, where Downwinders breathed the radioactive clouds that blew across state lines. When I learned it was the world’s largest open-pit copper mine, I refused to believe it. Nobody digs a mine pit in plain sight of a major metropolitan area.

Nobody, that is, except the enemy. On October 26, 1862, Colonel Connor planted the Fort Douglas flag on a hill overlooking Salt Lake City, signaling the United State government’s resolve to end the “Mormon problem” once and for all. To the feds — already embroiled in the Civil War — securing the provisional State of Deseret represented not only a strategic maneuver, but also a slap across Brigham Young’s face. To them — with his fifty wives and Danite henchmen slitting apostate throats in the dark — Brigham Young may as well have been the devil. Colonel Connor knew the self-proclaimed peculiar people could not survive the encroachment of Babylon, so he hatched a plot to lure Gentiles to Deseret. “You strike gold,” said Fort Douglas Military Museum Director Robert Voyles in the Salt Lake Tribune, describing Connor’s thinking, “how fast can you get gentiles?”

And even though Utah never spawned a California-scale gold rush, it did yield copper and silver — enough to make some Gentiles rich — as well as coal and uranium. Now 8,000 to 11,000 abandoned mines and 17,000 unguarded tunnels haunt this landscape. Since 1983, ten people have died falling into shafts, and twenty-six more have been injured. Stay out and stay alive, the Utah Bureau of Land Management admonishes, and though I know it is a public safety campaign, I get the sense something lurks beneath that warning, a double entendre.

Perhaps this is why mining particulates are called fugitive dust.

But here is the thing: Brigham Young not only let the mine happen; he helped it happen. He lobbied for the Transcontinental Railroad to meet at the Golden Spike. The railroad would bring Mormons into Zion, but it would bring Gentiles, too, and Gentiles would not defend Zion’s crystalline structure. Gentiles would be a force of entropy. He had to know the railroad would also speed trade, which of course included the mines. “If we were to go to San Francisco and dig up chunks of gold or find it here in the valley it would ruin us,” he said. He knew.

In 1974, Kennecott constructed the Garfield smelter tower 1, 215 feet tall, equivalent to three LDS World Headquarters office buildings stacked one atop the other: a modern-day Babel.

For 84 days, cement trucks worked around the clock, echoes of ox teams hauling granite from Little Cottonwood Canyon to build the Salt Lake Temple. To this day, the Garfield smelter remains the tallest man-made structure in Utah, designed to reach high enough in the sky to spit out pollution where it can blow away on the wind and meet the standards of the Clean Air Act. It is taller than the Las Vegas Stratosphere. Taller than the Seattle Space Needle.

With new efficiencies and cleaner emissions, the smelter no longer needs to stretch so high into the sky, but Kennecott has no plans to tear it down. It has become a kind of beacon for boaters on the Great Salt Lake and drivers on Interstate 80.

As long as you can see the smelter tower, you are never lost.

From a perch on the second story of a downtown parking lot, I can make out the walls of the Bingham Canyon crater, not the massive open pit where Kennecott shovels 450,000 short tons of earth every day. I squint, trying to make out the 320-ton capacity Komatsu trucks. With tires 12 ½ feet tall and bodies 29 feet wide and 51 feet long, they ought to be visible here, 27 miles to the northeast, like little remote-control trucks in a sandbox.

I can blame Brigham Young, but my people — the Gentiles — absconded with the land. What is the atonement for that?

Fugitive dust penetrates the deepest pockets of the lungs, lodging forever in the alveoli. I breathe in the mine dust, and within my wet flesh it becomes mud, which I exhale as water. It evaporates in the Zion sun and returns to the air. I transmute it. But I can never breathe it all the way out. It is part of me now. I am the fugitive dust. The fugitive dust is me.

After we shake hands, Bowen, Air Monitoring Manager at the Hawthorne Station, steps back as I photograph the two research sheds. I am surprised by how primitive they look, like meat lockers air-dropped in a snow bank. Were it not for the Hawthorne School playground just a few feet to the west, I might mistake the bare-bones setup for an Arctic research station.

The Division of Air Quality chose this location because of the school’s wide-open playground, but it has an added benefit: Children are most susceptible to asthma, so if scientists monitor the air where they play, they can protect the littlest lungs. The city contains better and worse pockets of pollution, so in this moment, I am sharing the same pocket as our little canaries in the coalmine. The canaries are nowhere to be seen; outdoor recess is canceled on red-alert air days. We are into Day Ten of the Mother of all Inversions, and I am struggling to inhale enough oxygen through my honeycomb charcoal-filter mask.

“You mentioned you’re a writer,” Bowen says. “You a reporter?”

“No,” I say, pulling down my mask so he can hear my raspy voice. “I’m a creative writer.” I don’t feel like explaining creative nonfiction, so I stop there.

“Good,” he says. “I mean — ” He steps closer, leans in, and knits his fingers together. — “we have to log all our interactions with reporters.”

We stand side by side, watching the wind-speed and direction instruments spin, slowly, as though underwater. It is hard to believe there is any wind at all.

“Want to take a tour?” He points to the two shed-like structures.

I walk with him, listening to the station buzz like a fly too close to my ear. I did not expect it to make so much noise. I did not expect it to be electric. I always pictured giant HEPA filters hung up on flagpoles, passive and silent. Then I realize: That I can hear it at all means it must be buzzing ten times louder on the other side of its smog muffler.

I follow Bowen up the stairs, feeling the vibrations of the humming trailers, and wonder how much electricity is required to keep this station running. Electricity contributes to inversion air because of the power-plant emissions.

On the way up, I glance at a playground slide, its red, blue, and yellow as brilliant as a Superman costume against the brownish-gray sludge in the air. “Do the kids pester you in the lab?” I ask.

“No,” Bowen says, shrugging, already at the top of the stairs. “They pretty much ignore us.” He looks resigned, maybe a little sad.

“If I were a little kid at this school,” I tell him, “I would bug you every recess.”

He shrugs again, and I glance at the slide one more time.

The kids are steeping in it.

On the roof, I can peep into the backyards of several houses behind the school. I wonder if those people have any idea what these air-dropped meat lockers do — if they realize that when they log into the Utah Air Quality site that the reading is literally their air.

When Bowen opens one of the machines and removes a stack of filters, I am shocked at how tiny they are, like stacks of tiddlywinks or poker chips.

He shuffles them in his palm, and I imagine all those bright red and blue plastic rings piling up in a landfill. As the filters degrade, the particulate disperse into the soil. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. When desert winds kick up Utah’s parched earth, are they stirring pollution right back into the air?

“Do you keep them?” I ask, gesturing to the filters. “I mean, when they’re used?”

“We throw them away,” he says.

“No recycling?”

“No.”

Of course, even if they recycled them, where would the particulates go? Clean them out of the honeycombs and dump them in the dump. Either way, we are burying the problem.

I think about the charcoal mask I am wearing, and how I will throw it in the garbage when its nooks and crannies are crammed full. I think about the carbon and zeolite HEPA filter I stuffed in the trash bin this morning after installing a fresh one. We are burying the air in the earth.

Is air monitoring sustainable? Is protecting our lungs sustainable? Is breathing sustainable?

And then I remember: My filters work by adsorbing particulates — not simply absorbing, but adsorbing, too — meaning the filter and molecules are attracted: like to like.

Bury those filters, I think. Let them fill up a landfill. Let like attract like. Let Zion do it to itself.

By the time Utah doctors implore Governor Herbert to declare a public-health emergency because of the bad air, it is already too late for me. Sometimes my lungs feel like helium balloons, and no matter how hard I exhale, I cannot force out the air. I gasp and gasp until I am certain my lungs will pop. People always think of breathing as inhaling, but the body does not inhale because it needs air; it inhales because of too much carbon dioxide in the blood. In this sense, breathing means expelling poison. I cannot expel this poison.

The asthma doctor confirms it, pointing to my pulmonary function report and declaring, “You had trapped air in your lungs.”

“A mini-inversion,” I say, my voice barely a whisper. The pollution has damaged my vocal cords, too.

“Exactly,” he says. “Particulates and all.”

I consider this for a moment, how I am a microcosm of Zion now. What does that mean for a Gentile?

He seems to sense my confusion. “What you have is called extrinsic asthma,” he says, “meaning it does not come from within you. It is not part of you. It was triggered by something external.”

I want to tell him he is wrong, that my asthma is intrinsic. I want to tell him about the cloud computer, the intelligent design, the atonement. I want to tell him about the temple, how it is yanking heaven down to Earth. How some of us cannot breathe the atmosphere in Kandor, and that is intrinsic. I want to confess about the mine, how I have been looking at ads for the Daybreak housing development at the base of it, even though — because I know — the fugitive dust will be worse there. How like attracts like.

Instead, I nod and tell him I will inhale a steroid medication through an aerochamber and wear my honeycomb mask. I tell him I will buy a new HEPA filter. I tell him I will beat this, even though I know I have already succumbed.

I am the fugitive dust. The fugitive dust is me.

“What if I leave?” I ask.

“You might get better. You might not.”

“If I don’t get better, does that mean it was intrinsic?”

“How wonderful would it be if all you had to do was leave?”

Get out.

Family and friends, witnessing the Mother of all Inversions on national television, urge me — beseech me — to move out of Utah, to move back home, to move anywhere but here. “We have clean air in Minnesota,” an old high-school friend posts on my Facebook wall. “We have clean air in Iowa,” my family back home writes. “Come home.”

Get out.

I tell them my husband and I are searching out-of-state job boards. I tell them we are apartment hunting. I tell them we are making plans.

I tell them I am running a HEPA air purifier twenty-four hours a day.

I tell them I am inhaling my asthma meds, staying indoors on red-air days, and taking my vitamins. That I am eating dark chocolate daily, as Utah doctors recommend, that the antioxidants will shield me.

I do not tell them this: that I suspect they want to save me from conversion, not inversions.

I do not tell them my sickness is intrinsic, that it is part of me.

I do not tell them about atonement.

I do not tell them that the sicker the air makes me, the more I want to stay.

In the thick, blue air of an inversion, I venture out for the first time in weeks. A man shuffles past me on the sidewalk, cradling a transistor radio. He adjusts the antenna and tucks his chin to whisper into the speaker: “Joseph Smith, yes, I can hear you now. The signal is clearer because of the air.”

Wow. This is really incredible. Did not see it the first time.